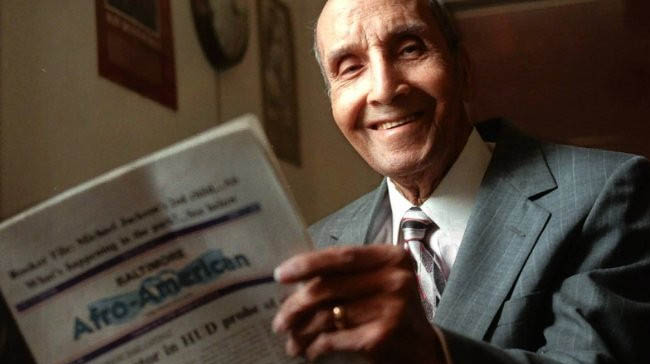

Sam Lacy spent the better part of seven decades fighting racial intolerance and used the power of his words as a journalist to pave the way for Jackie Robinson. His work as a reporter and his tireless support of equality for Black athletes ultimately changed the landscape of American sports.

“I had seen the teams come into play [the Senators],” he said shortly before his death in 2003. “Having seen these guys, I got to thinking that some of these ballplayers, watching them play, are no better than the guys that play in the Negro Leagues. It just didn’t seem proper or right.”

Born in Washington, D.C., Lacy grew up in the shadows of Griffith Stadium. His journalism career began as he was finishing his studies at Howard University. His pen fought for racial equality in sports, his voice among the first of a new breed of Black sportswriters.

“Baseball would accept anybody,” Lacy said. “Ex-convicts, anybody … I gave a lot of explanations in my stories about people who could be more undesirable than Black guys to the white ball clubs.”

Clark Griffith, the owner of the Washington Senators, was one of the first baseball officials Lacy spoke to about integration. Aside from success early in the mid-1920s and a World Series appearance in 1933, the Sens were perpetual doormats in baseball. Adding talent should have been a priority.

“I used that old cliché about Washington being first in war, first in peace, and last in the American League, and that he could remedy that [with integration],” Lacy said. “But he told me that the climate wasn’t right.”

Lacy moved to the Chicago Defender in 1940 and continued addressing the need for baseball to desegregate. His writing was rife with cuts at the white baseball establishment, and his voice was getting louder, inspiring other Black sportswriters to join the cause. Even prominent white sportswriters, including Shirley Povich of the Washington Post, began addressing the grievous inequality in baseball.

By 1944 Lacy had secured a stable of Black sportswriters with a voice loud enough to petition Major League owners. Together, they sought answers surrounding the perceived lack of interest in bringing Black talent to the majors. Nearly a dozen owners agreed to meet with members of the Black press, but only Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers kept his word and had a face-to-face with Lacy and other Black reporters.

Rickey collaborated with Lacy over the ensuing months and eventually, in October of 1945, inked Jackie Robinson to a deal with the Brooklyn Triple-A affiliate in Montreal. Less than two years later, Robinson broke baseball's color barrier making his debut with the Dodgers.

Lacy's new beat became Robinson and the Dodgers. He covered the team for three years, occasionally forced to work games from the dugout or grandstand because he could not sit in the press box designated for white reporters.

“It would have been a selfish thing for me to be concerned about myself and how I was treated,” Lacy said. "I did what I thought was right, and I believe it made a difference."